Photo Credit: Ontario Culture Days

What is the role of arts in advocacy and social movements?

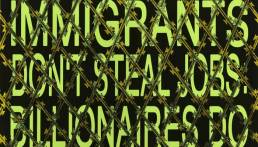

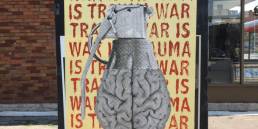

In conversation with Toronto-based artist and printmaker Jesse Purcell, 2021 Ontario Culture Days Creative-in-Residence Laura Rojas discusses the possibilities of radical graphics. In Laura’s words, these are visuals created at the intersection of art and design that are used to amplify the messages and demands of a community during protests and social movements.

"Because we are talking about radical graphics, I want acknowledge how using art as a form of protest was born from the struggle of oppressed peoples across the world"

Laura: We are going to be talking today about what is often referred to as radical graphics, or political/protest graphics. Apart from being powerful historical markers, these graphics serve to communicate, educate, and mobilize people into action.

Because we are talking about radical graphics, I want acknowledge how using art as a form of protest was born from the struggle of oppressed peoples across the world, who have long used various art forms during revolution, struggles for rights, land and water protection actions, and as a tool for resistance against oppression and attempted erasure, across history and today.

What do you think defines something as “political graphics” or “radical graphics”? Of course, aside from being overtly political in nature. I was reading an interview with Carol [Wells] from the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, and she was saying that for something to be included in their archive, it has to be created in a multiple. Do you think these graphics are something that have to live out on the street? Ahead of this conversation, we were talking about how digital mediums have influenced the way these graphics are shared— do you think that maybe there’s no need for these boundaries anymore?

Jesse: Well, they’re definitely blurring, and I think in the time of COVID it’s made people rethink. I know right now the Interference Archive in New York is doing a project of gathering digital images that have been created over the last year to support social movements because people have often been unable to be in the streets due to the pandemic. So, while I think there is a push to try to keep hold of all the more ephemeral ways of putting work out, I don’t see any need to really strongly distinguish it.

I think however, when the work is made out of tangible materials and distributed into people’s hands, it creates a real link to the social movement it’s trying to support. There’s a difference between making work about social movements, and making work in tandem with social movements— or about politics, instead of with the politics. So I think there’s a distinction there, between art-making that’s reflecting on the world, and art-making that’s intangibly supporting the voices of movements.

Laura: Beyond creating graphics to amplify a message and build solidarity, and working in tandem with other groups and organizations, what are other ways in which these graphics can play a role in popular education? I’ve seen a lot of the graphics you’ve created with Justseeds and in collaboration with other organizations and grassroots groups. I’m thinking of the Celebrate People’s History posters that Justseeds does.

What do you think are other ways that these graphics can break out of just being graphics and also influence what’s going on?

Jesse: I think that they have the capacity to keep histories of resistance or struggle alive, and also inform new generations about past struggle, creating a link between previous generations and previous struggles over similar issues— or the exact same issues, in some cases. I also feel that it keeps the idea alive in people’s minds outside of a day of protest or action; it keeps this idea of a continual struggle— both over history but also in daily life— for people who are actively struggling in those movements, or those who support it.

Laura: Right, these graphics are here to keep the flame burning outside of a moment of immediate action.

Jesse: Yeah, I feel like sometimes it’s within an echo chamber, but I also think that it can serve as a way to activate conversation, and I think that’s really important to do— to just put something up in a public space, or even in a private space, with the goal of engaging with those around you.

Laura: I feel what you’re saying about an echo chamber, but again, graphics are so interesting— like, physical, printed matter— in the way that they can cross boundaries so easily. You can go paste something up at the public library, or in the lobby of an apartment complex, and people who are maybe not running in the circles that are creating the graphics are also exposed to them. As opposed to like, when work is shared on Instagram or something– it is a bit more of an echo chamber there. These printed things have the quality that they can escape that.

Laura: It’s possible that some people who are joining us reading this article are interested in learning more about this type of art form.

What are some other resources or groups that you’d recommend they check out?

Jesse: Well, both the Interference Archive and Center for the Study of Political Graphics have expansive websites to see both contemporary graphics and historical ones.There has been an incredible amount of material made in support of the Black Lives Matter movement which is definitely worth checking out.

Jesse: Onaman Collective makes amazing work— they’re Christi Belcourt and Isaac Murdoch, two artists that have produced political graphics in support of Indigenous self-determination and land and water resistance struggles, and have also started a culture and language camp north of Georgian Bay, near Elliot Lake. Their collective is both inspiring as a project and just incredible graphics that are having impact, not just locally but also globally.

Laura: I really admire their work as well. I also think it’s super cool that their graphics are available as free downloads, and they have a video on how to assemble your own banner to bring to a protest… Justseeds also does freely downloadable graphics, right?

Jesse: Yes, we also have a downloadable graphics section on our website where it’s all free and accessible and people can use them freely as long as it’s not for personal profit. It’s a massive resource. People often get in touch with us looking for graphic work— so if we don’t have something that already exists, then often someone is able to make that happen.

Laura: And that’s something you do as well with Repetitive Press, more locally.

Jesse: Yeah, I’ve done stuff in support of Idle No More, in support of Black Lives Matter in Toronto, different Indigenous organizing that’s happened here in the city. I also make the space available for people to come in directly and use it, pre-COVID of course. I try to teach workshops or burn screens for other public art builds that are happening in other spaces. I’ve also done work here around climate justice issues— that work, I’m not sure if it survived the studio flood. Luckily, stuff has been given to archives.

Just a note, if you are making politically graphic work, I highly recommend that you find a few places to send it to that are keeping this stuff, because you never know what will happen tomorrow!

Laura Rojas is a 2021 Creative in Residence for Ontario Culture Days. For her program, Laura will lead workshops on designing posters, encouraging community building and mobilization. A final event will have attendees sharing their creations both in local neighbourhoods and publicly online.

Jesse Purcell is a socially engaged artist and printmaker based in Toronto. He is a member of the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative and founder of Repetitive Press – Screen Printing and Design Studio, which focuses on providing hand-made graphic materials for cultural producers while working to support social movements.

Header credit: Laura Rojas

You can check out our full list of 2021 Creatives in Residence here.